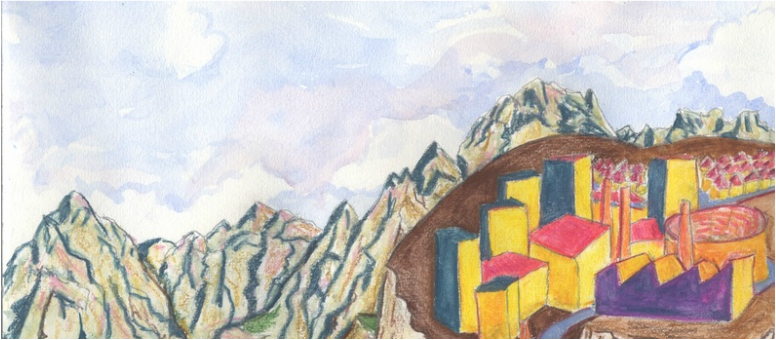

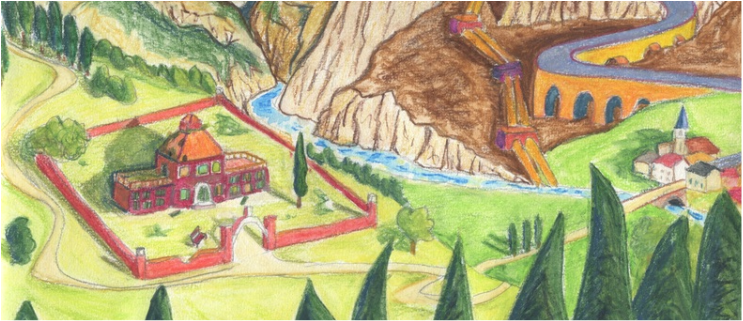

'The Mountain Giants' (October-November 2012)

'The language of this most impressive student production [...] immediately struck one as being very appropriate and effective. There were comments from the audience at the end to the effect that that there was something almost Shakespearian in the rhythm of the language'

'What emerged very effectively right form the start was the visual aspect of the set, with the changing light, against which one heard the contrasting voices - some shrill, some deep - of the characters: particularly noteworthy were the opposing voices of Sgricia, one of the Scalognati, and of Countess Ilse. So the audience was treated to a very original use of the visual and the auditory. All this, of course, accompanied Pirandello's concern with the role of art in contemporary society. The travelling actors are trying to stage the work of a young poet who killed himself for love of Ilse, and this work turns out to eb Pirandello's own La favola del figlio cambiato. Apart from this play-within-a-play there were very effective stage devices such as four puppets, two female, two male, with their completely immobile bodies which, combined with their false faces, had the audience wondering, until they jerked to life, whether they were not entirely artificial. Pirandello's elaboration of the conflict between reality and illusion, which in his earlier plays had a more human touch, here in this Myth has rather an otherworldly aspect, skilfully brought out by the production. This emerged admirably at the end, where the action was engineered, thanks to a wedding feast, so that there were no actors left on stage. They were all behind the curtain, and we, the audience, felt that were on stage and that we had not performance to applaud. This was a very effective Pirandellian ending!

Professor Laura Lepschy of University College London, for Pirandello Studies Journal (vol 33, 2013)

'What emerged very effectively right form the start was the visual aspect of the set, with the changing light, against which one heard the contrasting voices - some shrill, some deep - of the characters: particularly noteworthy were the opposing voices of Sgricia, one of the Scalognati, and of Countess Ilse. So the audience was treated to a very original use of the visual and the auditory. All this, of course, accompanied Pirandello's concern with the role of art in contemporary society. The travelling actors are trying to stage the work of a young poet who killed himself for love of Ilse, and this work turns out to eb Pirandello's own La favola del figlio cambiato. Apart from this play-within-a-play there were very effective stage devices such as four puppets, two female, two male, with their completely immobile bodies which, combined with their false faces, had the audience wondering, until they jerked to life, whether they were not entirely artificial. Pirandello's elaboration of the conflict between reality and illusion, which in his earlier plays had a more human touch, here in this Myth has rather an otherworldly aspect, skilfully brought out by the production. This emerged admirably at the end, where the action was engineered, thanks to a wedding feast, so that there were no actors left on stage. They were all behind the curtain, and we, the audience, felt that were on stage and that we had not performance to applaud. This was a very effective Pirandellian ending!

Professor Laura Lepschy of University College London, for Pirandello Studies Journal (vol 33, 2013)

'A few years before his death, Pirandello began his last play, The Mountain Giants. It was to be, I am told by this version’s translator, his most complete manifesto for drama, its qualities and its place in society. He never finished it; perhaps he could not bring himself to because of the nature and great importance of such an undertaking.

It is a fairy-tale play, about a company of actors led by a count and his actress wife, and their arrival among the Scalognati. These latter are an assembly of grotesques – a dwarf, a magician, an old woman who believes herself to be dead, who live in a villa where the creatures of one’s imagination become real, made so by Cotrone the conjuror’s doing that seems half real magic and half stage magic. Puppets move with no puppeteers, a young actor may seem a poet who died for love, an angel (and who knows whether he is real or not?) may lead through the country a hundred and one souls from Purgatory. The company, forlorn and less than half the number they used to be, are to act in the town nearby for the Mountain Giants, a people so called because of their size and the apparent awe the Scalognati hold them in.

This is an ambiguous work of advocacy for the life lived closer to the surreal, or a state where the Romantic imagination has conquered reason, where “our wishes [are] expressed by our eyes themselves”. It is a treatise on the making of art, poets who “give coherence to dreams”, and it is the instruction for actors: “learn from children who invent the game...and live it as if it were real”. In the last respect we may find it too explicatory, too much like an essay on stage, but as for the rest it is admirably done. The play is itself the imagined existence it describes, in its rarefied, enigmatic prose (“at dawn we see into the future; at dusk into the past”) and in its sunset where a vision is narrated, or in the striking apparition of the eerie Magdalen, the red lady.'

'Julia Hartley, director and translator, provided an ending for the play. Apparently some productions have stopped where Pirandello’s writing stops, at the end of the third act (there are four). Here the fourth act was the performance for the Mountain Giants. These we find are drunken and uncivilised; they violently overcome the actors, defenceless, who are beaten up without even a proper fight and the play ends (the whole play that is, not just the play within a play). It is a very appropriate shock of the cruel; I saw in it a horrid exposition of the ordinary man’s incapacity to understand art, the inevitable humiliation and suffering of the artist. But there is nothing indulgent about it, and coming at the end of such a dream like play, and with the grandly named Giants turning out to be who they are, one could say it was grimly arch.

We had been told to believe in a beautiful, hallucinatory world, but now it has been destroyed without even being able to resist, no heroic last stand. It is very Pirandello.' Thomas Stell for the Oxford Theatre Review

It is a fairy-tale play, about a company of actors led by a count and his actress wife, and their arrival among the Scalognati. These latter are an assembly of grotesques – a dwarf, a magician, an old woman who believes herself to be dead, who live in a villa where the creatures of one’s imagination become real, made so by Cotrone the conjuror’s doing that seems half real magic and half stage magic. Puppets move with no puppeteers, a young actor may seem a poet who died for love, an angel (and who knows whether he is real or not?) may lead through the country a hundred and one souls from Purgatory. The company, forlorn and less than half the number they used to be, are to act in the town nearby for the Mountain Giants, a people so called because of their size and the apparent awe the Scalognati hold them in.

This is an ambiguous work of advocacy for the life lived closer to the surreal, or a state where the Romantic imagination has conquered reason, where “our wishes [are] expressed by our eyes themselves”. It is a treatise on the making of art, poets who “give coherence to dreams”, and it is the instruction for actors: “learn from children who invent the game...and live it as if it were real”. In the last respect we may find it too explicatory, too much like an essay on stage, but as for the rest it is admirably done. The play is itself the imagined existence it describes, in its rarefied, enigmatic prose (“at dawn we see into the future; at dusk into the past”) and in its sunset where a vision is narrated, or in the striking apparition of the eerie Magdalen, the red lady.'

'Julia Hartley, director and translator, provided an ending for the play. Apparently some productions have stopped where Pirandello’s writing stops, at the end of the third act (there are four). Here the fourth act was the performance for the Mountain Giants. These we find are drunken and uncivilised; they violently overcome the actors, defenceless, who are beaten up without even a proper fight and the play ends (the whole play that is, not just the play within a play). It is a very appropriate shock of the cruel; I saw in it a horrid exposition of the ordinary man’s incapacity to understand art, the inevitable humiliation and suffering of the artist. But there is nothing indulgent about it, and coming at the end of such a dream like play, and with the grandly named Giants turning out to be who they are, one could say it was grimly arch.

We had been told to believe in a beautiful, hallucinatory world, but now it has been destroyed without even being able to resist, no heroic last stand. It is very Pirandello.' Thomas Stell for the Oxford Theatre Review

‘The Mountain Giants’ is the result of director Julia Hartley’s translation of Luigi Pirandello’s ‘I giganti della montagna’, with a final act noticeably penned by Hartley herself. We meet a Count and Countess with the remnants of their starving acting troupe arriving at the magician Cotrone’s enchanted villa; inhabited by a dwarf, a recently converted ‘Turk’ and a lady who seems to have borrowed Mary Poppins’ flying umbrella. Characters’ motivations are confusing and you are unsure most of time whether you are meant to be taking what they say seriously – in short, a lot of things don’t add up: cue some interesting theatre.

Catherine Haines, as the Countess who inspires both awe and disdain, was easily the most convincing performer. However, mentions must also go to Olivia Madin, Matija Vlatkovic and Ben Currie – whose performances were delivered with such energy and commitment to avoid being lost amongst the large ensemble. Sam Young was given the hardest task in terms of presenting the “mouthpiece for a complex discourse on the human imagination” (as Hartley describes Cotrone) and though the speeches were beautifully translated, and Young’s performance was watchable, ultimately more could have been done on his part to do justice to the character.

It was a shame that a few sound effects cut off abruptly, the ‘voice-over puppets’ were too quiet and the lighting monotone for the first act (though I understand this may have been dictated by the stage directions Hartley valiantly committed to stay true to) but it did mitigate the impact of the innovative sound design and meant the performance was slightly obfuscated at points. That said, I loved Nathan Klein’s eerie yet soothing music (please send those tracks over) and the set was impressive (the mountains and villa constructed for the first half disappear after the interval, hats off to the production team for making that happen!) the costumes lovely, and the overall aesthetic well presented – helping me very much to play along with this intentionally self-conscious ‘storybook’ world.

What is clear is that this production was a team effort, one they should be proud of, and one I urge people to go and see – despite any faults, it is a project whose ambition deserves support – I’ve not seen something like it in a while.' Roxy Rezvany for the Oxford Tab

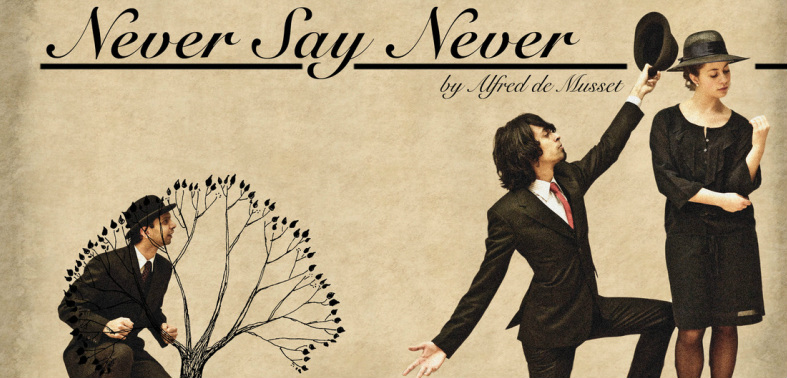

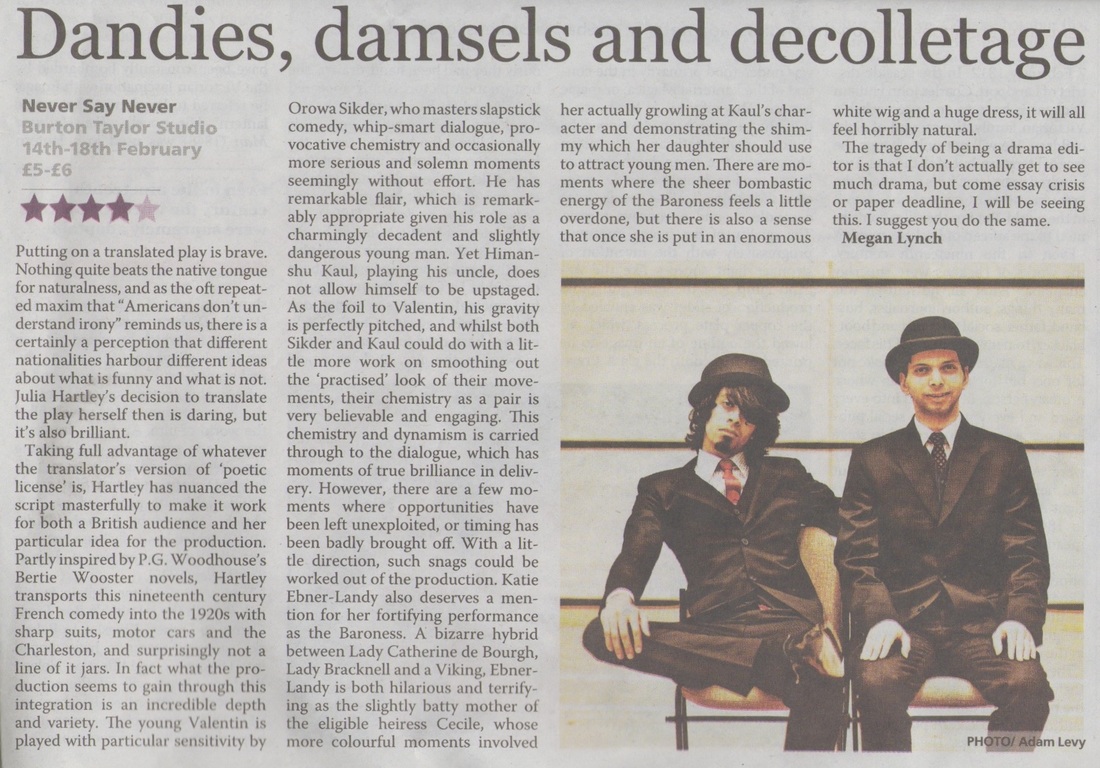

'Never Say Never' (February 2012)

From Page to Stage Victoria Weavil muses on translation in the theatre

Translation is a complex task at the best of times. The act of translation carries a whole series of conundrums: how important, for starters, is fidelity to the original text? To what extent - if at all - can a translated text reproduce the unique voice of the original author? And how can the distinct rhythms and modulations of a particular language possibly be reproduced in another language? Since each and every language bears its own unique character, history, and cultural baggage, the translator’s job will certainly never be an easy one.

Yet translating theatre brings a whole extra set of thorny issues to the table. For on top of the unending panoply of difficulties faced by translators of all kinds – from translators of the literary greats, to those faced with the apparently simple task of translating IKEA furniture instructions or restaurant menus – the theatre translator has an extra factor to worry about:performability. A theatrical script does not only need to flow. It needs to quite literally breathe with performability. To quote the Italian dramatist Luigi Pirandello, ‘in order for the characters to jump alive and moving off the written page, the playwright must find that word that is spoken action, the living word that moves, the immediate expression, natural to the action, the unique expression that cannot be but that one.’

The language of theatre is designed to be spoken, not studied. And a script that is rigorously faithful to the original – however commendable such an effort might be - is therefore unlikely to do the job.

And it is in this respect that Julia Hartley’s new translation of Alfred de Musset’s Il ne faut jurer de rien (1836) truly shines: It is hugely, unquestionably performable.

Yet translating theatre brings a whole extra set of thorny issues to the table. For on top of the unending panoply of difficulties faced by translators of all kinds – from translators of the literary greats, to those faced with the apparently simple task of translating IKEA furniture instructions or restaurant menus – the theatre translator has an extra factor to worry about:performability. A theatrical script does not only need to flow. It needs to quite literally breathe with performability. To quote the Italian dramatist Luigi Pirandello, ‘in order for the characters to jump alive and moving off the written page, the playwright must find that word that is spoken action, the living word that moves, the immediate expression, natural to the action, the unique expression that cannot be but that one.’

The language of theatre is designed to be spoken, not studied. And a script that is rigorously faithful to the original – however commendable such an effort might be - is therefore unlikely to do the job.

And it is in this respect that Julia Hartley’s new translation of Alfred de Musset’s Il ne faut jurer de rien (1836) truly shines: It is hugely, unquestionably performable.

Never Say Never follows the story of young playboy Valentin who – convinced that all married women are unfaithful to their husbands – sets out to do everything in his power to avoid any such a fate. Yet when his uncle entreats him to consider marrying the charming young Mademoiselle de Mante, Valentin proposes a wager that is intended to trick the Mademoiselle and prove his conviction right. But Cécile looks set to have the upper hand…

So, why Musset? And why this play? Asked about the reasoning behind her choice, Hartley explains that, of all Musset’s works, this is ‘by far his snappiest work’. And if we are able to enjoy this snappiness in full in Never Say Never (and we certainly are), this is thanks not only to the merits of the original but to Hartley’s methods of adaptation and translation. The original has undergone considerable shavings and additions before reaching its final form. Hartley explains that ‘by translating the play myself I have taken advantage of the process to cut the jokes that sound too long, and emphasise the traits which I have found more suited to a modern audience.’ Take her translation of the title, for example, which is far snappier than the relatively weak ‘You Can’t Be Sure of Anything’ plumped for by previous translators of the play. Punchy and to the point, Never Say Never captures the full spirit of the original in a way that ‘You Can’t Be Sure of Anything’ just doesn’t quite manage.

But how about the humour? Can the wordplay, playful innuendos, and caricatures that characterise 19th century French theatre really get a modern-day English audience going? The answer is a resounding yes. And this is thanks to three key achievements: a successful translation, innovative adaptation choices, and masterful acting on the part of the cast.

Humour is absolutely fundamental to the success of this play, and it is perhaps here that Hartley’s translation deserves greatest praise. For comedy often sits ill at ease outside its own native territory. And matched perhaps only by the challenge of translating puns and linguistic nuances, it represents one of the greatest trials for the translator. Hartley explains that in this reproduction, while 'there are some classic moments where the comedy comes from the situation which will always work', most of the humour derives from the direction: 'It’s to do with the timing, the physicality, the tone of the delivery. A funny script, if it’s done in a dull way, loses all its potential'. Yet equally important to the successful deliverance of humour is Hartley’s appreciation of the importance of succinctness in English. For if Romance languages are characterised by their long, meandering phrases and elaborate phraseology, English is a language of concision. Hartley recalls herself 'laughing out loud when reading a Wodehouse dialogue which consisted mainly of “No.” No, no, no.” “Rather.” “Yes.”' Favouring succinctness over long-windedness, Never Say Never captures the spirit of the original’s humour while delivering a powerful punch designed to please an English audience.

The decision to transpose a 19th century French play to a 1920s Wodehousian setting is certainly a brave one. Yet in cleverly refashioning the style and language of the original into a distinctly modern form which is faithful to the spirit if not the letter of the original, Hartley manages to get the balance between fidelity and modernity just right. A refreshing take on a little-known 19th century classic that is not to be missed!

Victoria Weavil for Cherwell Online, 16th of February 2012

So, why Musset? And why this play? Asked about the reasoning behind her choice, Hartley explains that, of all Musset’s works, this is ‘by far his snappiest work’. And if we are able to enjoy this snappiness in full in Never Say Never (and we certainly are), this is thanks not only to the merits of the original but to Hartley’s methods of adaptation and translation. The original has undergone considerable shavings and additions before reaching its final form. Hartley explains that ‘by translating the play myself I have taken advantage of the process to cut the jokes that sound too long, and emphasise the traits which I have found more suited to a modern audience.’ Take her translation of the title, for example, which is far snappier than the relatively weak ‘You Can’t Be Sure of Anything’ plumped for by previous translators of the play. Punchy and to the point, Never Say Never captures the full spirit of the original in a way that ‘You Can’t Be Sure of Anything’ just doesn’t quite manage.

But how about the humour? Can the wordplay, playful innuendos, and caricatures that characterise 19th century French theatre really get a modern-day English audience going? The answer is a resounding yes. And this is thanks to three key achievements: a successful translation, innovative adaptation choices, and masterful acting on the part of the cast.

Humour is absolutely fundamental to the success of this play, and it is perhaps here that Hartley’s translation deserves greatest praise. For comedy often sits ill at ease outside its own native territory. And matched perhaps only by the challenge of translating puns and linguistic nuances, it represents one of the greatest trials for the translator. Hartley explains that in this reproduction, while 'there are some classic moments where the comedy comes from the situation which will always work', most of the humour derives from the direction: 'It’s to do with the timing, the physicality, the tone of the delivery. A funny script, if it’s done in a dull way, loses all its potential'. Yet equally important to the successful deliverance of humour is Hartley’s appreciation of the importance of succinctness in English. For if Romance languages are characterised by their long, meandering phrases and elaborate phraseology, English is a language of concision. Hartley recalls herself 'laughing out loud when reading a Wodehouse dialogue which consisted mainly of “No.” No, no, no.” “Rather.” “Yes.”' Favouring succinctness over long-windedness, Never Say Never captures the spirit of the original’s humour while delivering a powerful punch designed to please an English audience.

The decision to transpose a 19th century French play to a 1920s Wodehousian setting is certainly a brave one. Yet in cleverly refashioning the style and language of the original into a distinctly modern form which is faithful to the spirit if not the letter of the original, Hartley manages to get the balance between fidelity and modernity just right. A refreshing take on a little-known 19th century classic that is not to be missed!

Victoria Weavil for Cherwell Online, 16th of February 2012

'Counting Syllables' (August 2011)

" Ionian Productions’ charming exploration of the complexities of human relationships begins and ends with the interaction between audience and performer. Before the show starts Orowa Sikder, who will play the part of performance poet Razeen during the show, chats with members of the audience about why they’ve come to see the play. He asks each of us to tell him an interesting fact about our lives which we are happy to share with the group. Right at the end, Orowa/Razeen takes to the floor and turns these pieces of information into a poem which becomes play's conclusion.

The sense of a link between audience and performer was further strengthened by the choice of venue: the basement bar of the Phoenix contains a very small audience space which the actors work directly alongside, and sometimes within. The intimacy of the set facilitates a sense of mutual scrutiny – at times I wasn’t sure who was made more uncomfortable by this - and helps the sense that this play is exploring the idea of love in real life, rather than a glamorous or theatrical version. Julia Hartley’s script explores the varieties of emotional relationship possible between Camille, a university student, her thirty-something womanizing lecturer Richard, and Richard’s flatmate and fellow academic Thomas. The script particularly focuses on the role of academia in such affairs: Richard impresses Camille with his critique of her sonnet, and she seems vulnerably naive when she admits to only being able to write them if she counts the syllables on her fingers. Later, however, Richard proudly proclaims to Razeen that he only started writing poetry ‘to get laid’, and Tom calls Richard an ‘abuser’ of culture.

Fiamma Mazzocchi Alemanni’s tight direction means the small cast flourishes in their representation of the changing dynamic between the three central characters. At points of tension the small domestic spaces of Richard and Tom’s flat become claustrophobic centres of emotional conflict. The strong cast all possessed good vocal modulation and movement was well controlled. Himanshu Kaul as Tom was particularly nuanced in his emotional expression, and Christopher Hinchcliffe was disarmingly convincing in his portrayal of the baby-faced, manipulative Richard. At times the actors’ delivery sounded a little stilted, but they inhabited the dialogue more fully as the play progressed. This skilfully-wrought production is romantic without being simplistic, and highly recommended. "

Annabel James for edfringereview.com

The sense of a link between audience and performer was further strengthened by the choice of venue: the basement bar of the Phoenix contains a very small audience space which the actors work directly alongside, and sometimes within. The intimacy of the set facilitates a sense of mutual scrutiny – at times I wasn’t sure who was made more uncomfortable by this - and helps the sense that this play is exploring the idea of love in real life, rather than a glamorous or theatrical version. Julia Hartley’s script explores the varieties of emotional relationship possible between Camille, a university student, her thirty-something womanizing lecturer Richard, and Richard’s flatmate and fellow academic Thomas. The script particularly focuses on the role of academia in such affairs: Richard impresses Camille with his critique of her sonnet, and she seems vulnerably naive when she admits to only being able to write them if she counts the syllables on her fingers. Later, however, Richard proudly proclaims to Razeen that he only started writing poetry ‘to get laid’, and Tom calls Richard an ‘abuser’ of culture.

Fiamma Mazzocchi Alemanni’s tight direction means the small cast flourishes in their representation of the changing dynamic between the three central characters. At points of tension the small domestic spaces of Richard and Tom’s flat become claustrophobic centres of emotional conflict. The strong cast all possessed good vocal modulation and movement was well controlled. Himanshu Kaul as Tom was particularly nuanced in his emotional expression, and Christopher Hinchcliffe was disarmingly convincing in his portrayal of the baby-faced, manipulative Richard. At times the actors’ delivery sounded a little stilted, but they inhabited the dialogue more fully as the play progressed. This skilfully-wrought production is romantic without being simplistic, and highly recommended. "

Annabel James for edfringereview.com

'Stendhal's The Red and the Black' (February 2011)

Poster design by Alan Rimmer

"It is a tactfully directed performance by Julia Hartley, the actors making full use of the stage set amidst the audience. Though it does not always allow the best view for people in the back row (get there early!), the stage allows the omnipresent, if not omnipotent, Stendhal to spring up from every angle, and also for some interesting bits of choreography, with characters able to fly on and off of the stage rapidly or come lurching out of the darkness in a more ominous manner.

The Red and the Black provides a prime example of how the beefier novels of the 19th Century can be adapted for the stage, though credit must also be granted to Burton for translating what is a challenging psychological novel so effectively into a play. What might have been just a quaintly amusing melodrama is subverted and undercut through Stendhal’s involvement to yield reams of irony and comedy that would not otherwise have been present, and make this fine adaptation a play well worth seeing." **** Chris Webb

"While it would be ludicrous to do so without the accompaniment of a coat, it would be equally ludicrous to miss out on both the very organic comedy this production offers, and the magnitude of attention to detail and inventiveness employed by both the writer(s) and director." **** Rosalind Stone

To read the full reviews, go to the Oxford Theatre Review's website .